Standards-based grading (SBG) aims to align grading with learning standards, but in practice, it often prioritizes content knowledge over skill development. While content mastery is important, it doesn’t always translate into real-world competence. This is where evidence-based grading (EBG) offers an alternative.

Educators can adopt evidence-based grading practices to address the shortcomings of standards-based grading (Reibel et al. 2025). EBG emphasizes developing competence in enduring skills supported by content knowledge, prioritizes student agency, shifts instructional and assessment cultures, and grades student work against proficiency standards rather than relying on algorithms and calculations (Clark & Talbert, 2023; Gobble et al., 2017; Reibel et al., 2024; 2025).

Shifting the focus in SBG – what really matters?

SBG could refocus on skill standards and place content standards in supporting roles for building broader competencies (Gobble et al., 2017). While content knowledge alone is not enough to create self-reliant individuals, skill competence is also important (Reibel et al., 2025). For example, the SBG curriculum could look like this:

- Skill Standard: Uses evidence effectively to support claims.

- Success Criteria (Content Standard): Knowledge of the main character in To Kill a Mockingbird.

- Skill Standard: Writes detailed equations to solve problems reliably.

- Success Criteria (Content Standard): Quadratics, completing the square, vertex form.

What will prepare students for life beyond K-12?

Schooling must prepare students for life beyond K-12 (Bandura, 1997, 2023; Hibbs & Rostain, 2019). Developing broader skill competencies, supported by content knowledge, prepares students for adulthood. Agency, efficacy, and competence must be cultivated during primary and secondary schooling, as they often predict post-K-12 success (Bandura, 1997, 2023; Hibbs & Rostain, 2019).

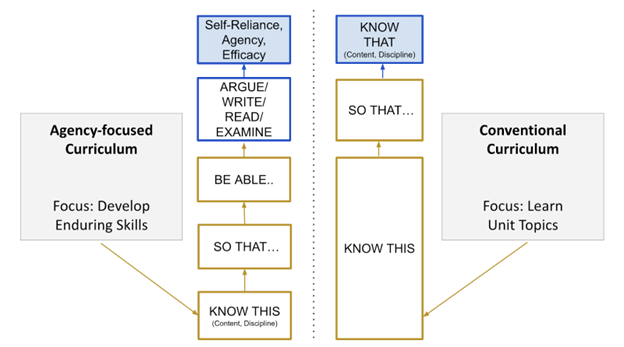

Figure 1 shows an agency-focused curriculum where skill competence, agency, and self-reliance are the ultimate goals (left) versus the traditional curriculum, often used in SBG, where content knowledge is the desired outcome (right).

Figure 1

Comparing Agency-focused Curricular Structure to Conventional Curricular Structure

The focus should be on purpose – not just scores

SBG frequently overlooks meaningful changes in assessment design. In EBG, teachers design assessments that evaluate content knowledge while simultaneously building skill competence. Summative assessments measure proficiency in a standard, rehearsal-style formative assessments (like scrimmages or dress rehearsals) build proficiency, and checks for understanding to deliver and reinforce foundational content knowledge (Bandura, 1997, 2023; Gobble et al., 2016). The only assessments that count toward the final grade are the summative assessments, evaluating final skill and knowledge proficiency (Feldman, 2023).

Use mode and trends instead of averages

A more reliable way to evaluate grades involves evaluating a body of evidence and identifying performance trends over time rather than relying on averages (Gilovich, Griffin & Kahneman, 2002; Gobble et al., 2017; Meehl, 1954; Kahneman, Sibony, & Sunstein, 2021). This includes conversations with students about their proficiency levels and determining final grades with them.

Organize gradebooks around learning stories

Traditional gradebooks track scores and calculate a final grade by recording homework, quizzes, and test scores, while EBG teachers organize their gradebooks around broader skills and track evidence of student learning stories (Gobble, 2017; Guskey, 2014; Hawe et al., 2021; O’Connor, 2017). Those four learning stories are:

- “How am I growing?” = Progress toward a standard

- “How am I doing?” = Proficiency levels in a standard

- “How am I preparing?” = Readiness for learning

- “How am I behaving?” = Classroom behavior

Pro tip: Focus on proficiency standards first and foremost

Standards, whether in education, industry, or daily tasks, establish benchmarks for quality or achievement. Merriam-Webster defines a standard as “something set up and established by authority as a rule for the measure of quantity, weight, extent, value, or quality.” Standards define the expected level of mastery of standard rather than just the content knowledge to be learned (Reibel et al., 2024, 2025). See example below:

- Proficiency Standard (expected level of proficiency): Write an effective argument with sufficient detail.

- Success Criteria (supporting standards to build proficiency): 1) compare and contrast details, 2) include appropriate organization, 3) analyze themes from the text. (Moss and Brookhart, 2012; Reibel et al., 2024, 2025)

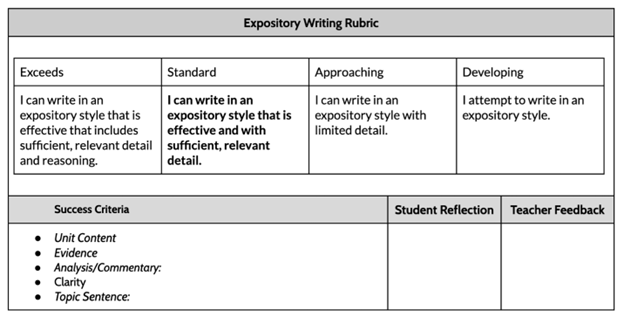

Distinguishing between proficiency scales and proficiency progressions is critical for meaningful grading change. Proficiency scales define mastery levels (e.g., exceeds, meets, approaching), while proficiency progressions outline actions that lead to mastery (e.g., list, define, explain, analyze). Confusing these two can lead to confusion with grade calculations and reporting.

3 powerful ways to scale standards

In addition to using DOK levels, there are other effective ways to scale standards. One way to scale standards is task complexity. This involves progressing from analyzing a basic text to a detailed text, then to an advanced text, and finally to an advanced text with complex themes. Another way to scale standards is on familiarity of context, progressing from a given situation to a familiar one, to an unfamiliar one, and finally to a novel situation. A third approach focuses on components, where the standard scale might progress from given components to relevant components, to essential components, and then to ideal components.

Why four levels? A better way to measure student growth

SBG rubrics often function as checklists of content and actions needed to achieve “meets” standards on a task. EBG uses single-skill rubrics to define expected proficiency and outline criteria clearly. Content standards act as criteria to support skill proficiency development with a four-level proficiency scale. Why four levels? A four-level scale is more appropriate for classifying competence (Colby, 2019), whereas five or more levels are better suited for classifying achievement (Marzano, 2011; Brookhart, 2013; Guskey, 2014, 2022). An example of an EBG rubric is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Single Skill, Four Level Proficiency Rubric

Why evidence-based grading is the better choice

Many grading reforms, like SBG, rely on outdated solutions to recurring challenges, failing to drive meaningful or lasting change. To create lasting change, schools can challenge grading illusions, align curriculum and assessment with agency and enduring skill competence, adjust instruction to focus on proficiency instead of content knowledge, and design rubrics with single-skill proficiency scales. If you’re looking for a grading system that encourages growth, evidence-based grading is the way forward.

About the educator

Anthony Reibel hails from Adlai E. Stevenson High School in Illinois and is the current assistant principal for teaching and learning. Anthony is also coauthor of several books: Proficiency-Based Assessment, Proficiency-Based Instruction, Proficiency-Based Grading in the Content Areas, and Pathways to Proficiency which explore the relationship between proficiency, pedagogy, and evidence-based grading.