“It makes it difficult, because the way school is set up, it has students working like machines. We get up early everyday to learn different things from 8 subjects, then forced to remember it in one day to move on to another subject the next day. It is exhausting. I go to school, I go home and study, I go back to school, and I repeat the process until I get so emotionally drained and mentally drained, that I want to give up…”

“Teachers give students a lot of buy-in. Students are not given hall passes or ID’s because there is a system of trust in place. Student and teacher relationships are also very unique, for many teachers act as mentors for the students. The teachers came to school early and leave late to ensure we have a place to learn and receive tutoring.”

Two quotes. Two points of view. Two feeling sets. Taken from high school student survey responses (2016), these two quotes show the world through different lens. The first pictures students as robots who are forced through the day to complete meaningless and mechanical tasks that deplete energy with boredom. That is the world where Casey’s strikeout left Mudville without joy.

The second gives a picture of the hometown fans after Casey hits a grand slam. It takes a celebratory tone so that everyone feels they are hitting grand slams every moment they are in school. In contrast with the strikeout school, every student here readily digs into the work they are doing as they collaborate and communicate, problem solve, investigate, and celebrate what and how they are learning. Mutual trust and mutual respect are hallmarks of the reciprocal relationships that predominate day in and day out.

What can we learn from such contrasting views? Each describes a different school environment. In the one, the school culture is toxic, poisoning students’ desire to learn. In the other, the school culture is nutritious, enriching students’ learning health. It is the latter that is a pre-requisite for making deeper learning alive in classrooms.

BRAINS STUDIES SUGGEST WHY.

Neuro-scientists, neuro-psychologists, and brain researchers have labeled the first example’s culture as “toxic.” In such a place, a poisonous atmosphere depletes student energy and desire to learn.

In Dr. Willis’ review of our survey’s full results she noted: “When joy and comfort are scrubbed from the classroom and replaced with homogeneity and conformity, students’ brains are distanced from effective information processing. In this school’s data, I find too many bored, anxious, and unengaged students. I see a passage taking students away from feeling good about learning and themselves. They have become discouraged, alienated, bored, intimidated, and overloaded with dogged, make-work curricula. This has created a climate of resistance, alienation, and discouragement.”

These key word descriptors not only contrast with the attitude of student responses illustrated by the second example, they denote how disrespect and distrust have a negative impact on students’ willingness to engage in learning. In fact, the achievement results from each school’s very similar students corroborates the hypothesis that a non-toxic, healthy environment contributes to outcomes that create results significantly superior to the non-favorable results of a toxic school. The joy of the second school is found in students able and willing to invest in making their own futures because their teachers empower them with trust through respect.

DIFFERENT WAYS TO TEACH AND LEARN

Whether toxic or healthy, a school’s learning environment is easy to identify. One only need look at the relationships between teachers and students and students with each other as they make evident the absence or presence of a positive reciprocal relationship. Students and teachers in a healthy school not only hear and see the sights and sounds of trust, they feel it. So too, those in a toxic environment with its poisonous relationships.

When a word analysis of students’ statements identify “reciprocal trust and respect,” “collaboration,” and “caring support” as the primary descriptors of the teaching-learning environment, student achievement climbs and students set goals and plan for their futures. (Bellanca, 2016). The same analysis identifies evidence-based best practices that support those terms. Researchers John Hattie and Robert Marzano have provided meta-analyses detailing the most effective strategies and their importance in creating a school where students are excited about learning.

On the other hand, the consistent use of words such as “intimidated”, “overloaded,” and “drained” connected to practices that have failed to produce positive feelings about school, tell us we are likely to find negative academic results as we observe instructional strategies shown to have low impact on achievement or are so random and episodic as to deter learning. Even when looking to the bottom of the researchers’ effect-size lists, one cannot find any indication that such shallow instructional tools as worksheets, lectures, or disrespect help students learn.

If the students in each of these two schools did not so closely mirror their ages, economic conditions, race, and ethnicity, one might conclude that the inherent student differences were the reason for different academic performances. Not so. With all other things equal, the positive, healthy climate allowed teachers and students to wade into the deepest learning waters and enjoy the fruits of instructional practices, which evidence tells us get the most powerful results.

DIFFERENT STROKES FOR DIFFERENT FOLKS.

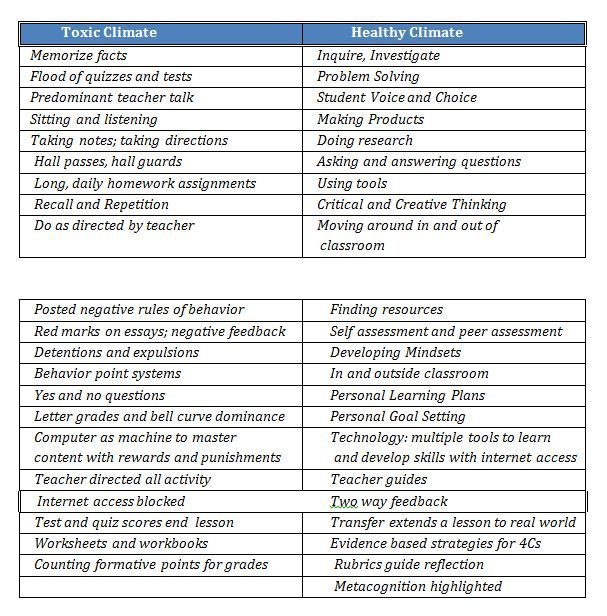

Examination of curriculum, instruction, and assessment practices tell us what makes a school’s climate what it is. Much is embedded in how teachers teach. These parallel lists show partial samples of learning activities and their connection with each climate:

The two schools in the survey are close to resembling the best of times and the worst of times. Over my years, I have seen most schools falling in between. Unfortunately, thanks a lot to the ravages and pressures of No Child Left Behind, the scales in too many schools are tipped to the toxic side. The good news is that the number of schools on the healthy scale are growing. Common sense reinforces the notion that students learn more deeply when teachers are allowed, prepared, and encouraged to tip the scales to the healthy side, the deeper learning side. IT’S COMMON SENSE.

Jim Bellanca brings his too many but never enough years of teaching, designing school innovations, writing, editing and professional development to focus on the renewal of schools as 21st Century Learning Places. Wearing multiple hats as founding editor of the P21Blogazine, editor and author with multiple presses, President of the Illinois Consortium for 21st Century Schools and Director of School Innovation for Asian Human Services, Jim focuses his energy on transforming schools into 21st Century Learning Places.

Next Month: More Joy in Mudville. Part II

[author_bio id=”145″]