Based on Literacy Reframed

Listen, and you will hear, the sounds of literacy ringing in your ears.

As human beings, we come pre-wired to learn language by hearing it spoken. The first sounds of language are even heard in the womb. Tiny ears recognize the sound of Mom’s voice, distinct from Dad’s. These first encounters are followed by the oral language of “baby sounds,” mimicking what they hear and reproducing their interpretation of the sounds that grow naturally into speaking.

Human beings are not, however, pre-wired for written language. Cognitive science reveals that the area of the brain associated with visual inputs, are not connected to the other two—sound and meaning. Teaching a child to read and to become highly literate, then, must connect these previously disconnected areas. Visual inputs—the symbols of letters and words on the page/screen—must be connected to sound and meaning.

The Sounds of Literacy

We frame this first, natural phase as “The Sound of Literacy.” Then, the more formal literacy development—the work of wiring together areas of the brain that are not naturally connected—begins the next phase, “The Look of Reading.”

The Look of Reading

This is where conversations of explicit and systematic phonics instruction begin. More recently the conversation has been framed as “The Science of Reading” to reflect the deep research base that supports this approach of phonics first. Then, vocabulary forever, building the schema of words and concepts that build background knowledge, the fruits of moving into literacy learning’s phase two.

It is imperative, however, to know how far this first phase can take us and how markedly different it is from the phase that must follow. Share (1995), frames phonics instruction as “the logical point of entry, since it offers a minimum number of rules with the maximum generative power,” (pg. 156). In this statement, “rules” are synonymous with “skills.” As is well-known, there are innumerable phonics skills to be explicitly taught, and although the first phase is a proven developmental phase that deserves high priority in early literacy, in this book, we chose not to delve into this deeply. There are a variety of exemplary resources to help on this front.

Some contend that we know more about reading and more about phonics than any other area of literacy acquisition. Another text on phonics will not contribute to the dialogue, but a better understanding of what comes after, the skills of “The Look of Reading,” will. In addition, advocating the undergirding role of “reading for knowledge” is critical for literacy learning.

Fourth Graders: Literacy Growth Begins to Flatline

This sequence is critically important because, up to Grade 4, U.S. students perform fairly well in reading. After that, however, growth begins to flatline. And this trend has been evidenced widely, for over 30 years (Joyce, 2017). Shifting this data picture to one of continuing reading/literacy growth through all the grades, mandates that we know more about this phase of literacy acquisition that comes on the coattails of phonics instruction.

To completely understand some missing elements in the full literacy acquisition process, it’s helpful to envision literacy acquisition’s two very different phases to realize full maturity in literacy excellence:

- The first phase currently goes quite well. It is what occurs consistently in most early grade classrooms—direct instruction for phonics. This teacher-directed phase is typified by things that must be deductively taught. At the same time, the appreciation and information gleaned from early reading offers students a wholeness of the entire experience of reading for meaning seeps into the daily exercises and as the peripheral reading-aloud episodes that punctuate the day.

- The second phase is very different. Significant portions of “the look of reading” involve students self-teaching. While the process of students tang the reins of reading can be guided and supported by teachers, the ultimate work is handled by students. Thus, we must learn to create and appreciate the conditions needed to develop a true sense of student agency in their literacy journeys.

Overskillification

The laser-like focus on skills fades considerably in phase two as students advance to the stage of words making meaning to the reader. Certainly, there are skills to be learned, but many current programs, instead of making the dramatic change over to meaning and understanding, continue the skill-and-drill curriculum past its needed effectiveness. This can result in overrunning precious reading and writing time with a stale curriculum of “overskillification.”

Rather, it’s time to acknowledge the shift from a skill-focused curriculum to one that develops fluency and comprehension. Schmoker (2018) advises, “Once students learn to decode, they learn to read better and acquire large amounts of vocabulary and content knowledge by reading—not by enduring more skills instruction” (p. 131).

Massive Amounts of Reading for Meaning: Knowingness

Importantly, Literacy Reframed carries a message of urgency regarding how to correct the flatlining in reading growth for our Grade 4-through-college youngsters and young adults. Voices represented in the text, tend to offer similar expert advice. Unequivocally, significant amounts of reading and writing must occur, for students to acquire vocabulary and knowledge for reading comprehension.

It’s called “The knowingness of reading,” and references the deep understanding of knowledge students take away from their reading endeavors across all disciplines.

After having done many hours of careful, collegial syntheses of the findings in reading achievement, the conclusion is that literacy needs reframing for students to represent the epitome of “a literate person.”

The alarm bells are ringing and solutions are not simple, nor quick. But solutions for learning literacy excellence are definitely, very doable. The time is now, to act urgently and profoundly to engineer instructional settings around great chunks of time, for students as readers and writers; listeners and speakers.

Decoding: Quick Wins to Try

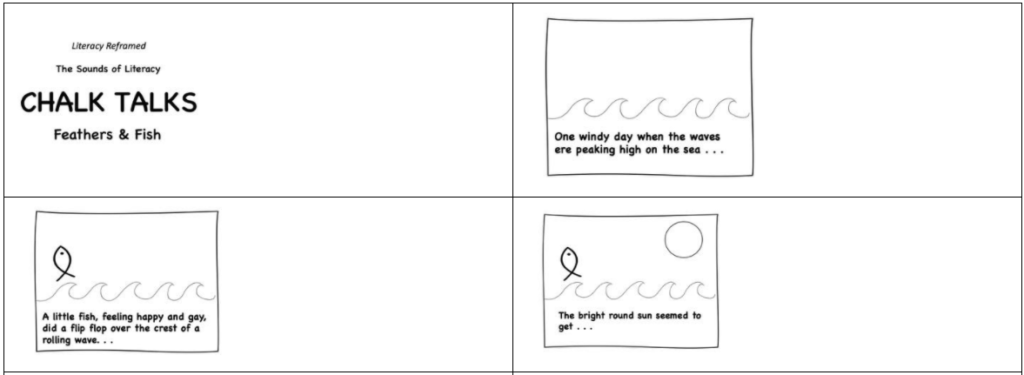

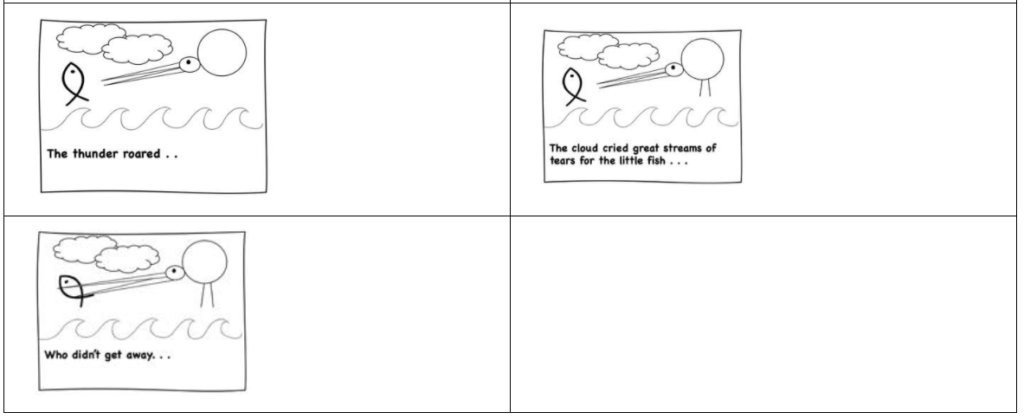

1. Chalk Talks: The Sounds of Literacy and the Hidden Mystery

PreK-3 Exercise

In early learning, teachers tell the “Chalk Talk” story aloud, accompanied by a progressive visual drawing, then evolves frame by frame to reveal a surprise ending of the hidden image.

A Chalk Talk: Feathers and Fish

*Note: 8 Chalk Talks in Literacy Reframed

II. Tongue Twisters: Pronunciation, Articulation

Grade 4-8 School Exercise

Tongue-twisters are fun, and they emphasize pronunciation of words, and articulation of phrases and sentences using the mechanics of alliteration. In some cases, tongue-twisters can be rigorous written assignments to review concepts within a particular discipline.

| Tongue Twisters: Pronunciation, Articulation

Try these for practice, and then try to write a tongue twister for one idea you learned in class:

6th Grade Assignment: Write a tongue twister about the laws of force and the weather. Fickle Tornadoes: “A Frightful Force Finds Farms, Fields and Far Away Forests for Fearful Frolicking.” (According to the Guinness Book of World Records, the toughest tongue twister is: “The sixth sick sheik’s sixth sheep’s sick.”) |

3. One-Minute Essay with Edit Panel

Grades 9-12 Exercise

Students fold a single sheet of paper. The topic is: Why I Remember Stories.

Teacher: “You have one minute to write as many words as possible about the topic. I will time you. Use complete sentences. Ready! Set! Begin!” (60 seconds go by.) Stop! Hold up your pens! Count the number of words you wrote. Circle 3-plus syllable words and make new word choices.”

One Minute Write

| #1 Stories-Narrative Words | Edit Panel: Circle 3 words, make better word choice.

1. 2. 3. |

| #2 Stories-Informational | Edit Panel: Circle one sentence; rewrite for clarity. |

In Closing

The sounds of language lead the way at the beginning of the Literacy Reframed journey with explicit teaching of phonics and their letter-sound and word-sound relationships. In turn, images of words matter to make meaning. Word sounds, word images, word knowledge. And that is simply the story of literacy learning, as Literacy Reframed becomes the norm in literacy instruction.

References:

Joyce, Bruce R. Weil; Weil, Marsha; Calhoun, Emily; Models of Teaching. Pearson, 2017.

[author_bio id=”53″]

[author_bio id=”341″]