Systems Thinking and Curriculum Differentiation

We recently visited an amazing South American tapas restaurant and were greeted with an extraordinary assortment of delicious and diverse foods. When presented with each subsequent platter, we could have taken one of two attitudes: eagerly welcome the array of these delicacies and appreciate their unique presentation and flavor or hesitate and refrain from indulging. To us, the more distinct the dish, the more we wanted to experience it. As educators, we feel the same about the dynamic and diverse individual needs we find in today’s classrooms.

Fisher and Frey (2015) do a great job of explaining the idea of systems thinking and synthesizing what it means for the 21st century teacher. Presently, the role of a teacher is that of a systems manager whose key responsibility is to leverage individual student abilities by breaking down the curriculum into digestible elements of learning. This is how systems thinking directly connects to the idea of curriculum differentiation. In a constantly changing classroom, the systems manager strives to co-evolve by not only changing one’s own instructional delivery but also transforming the curriculum itself. Effective curriculum differentiation means that educators seek to find individualized objectives (Brooks & Pineda Zapata, 2017), carve out innovative and adaptable approaches, and develop capacity in students through avenues of reorganization, flexibility, and creativity.

Differentiated Curriculum and Instruction: What Does This Mean?

Thousand, Villa, and Nevin (2007) emphasize that differentiation in the classroom should be approached by considering three key areas: content, process, and product. Thousand et al. (2007) skillfully define each of these terms below, and we provide some examples that may fall within these three critical components when planning for impactful differentiation within our classrooms.

Content

This involves not only the what of learning but what we aim for students to acquire from the content and how we present it.

- Step-by-step facilitation (numbering, chunking)

- Guided questioning

- Clear and purposeful samples and guides (parallel math problems, sentence frames, guided paragraphs)

- Visual representations of content (videos, PowerPoint presentations, social media)

- Presentation (be concise, define key terms, evaluate font size and spacing)

- Teacher-created screencasts of content being presented

Process

This focuses again on the how of learning but zooms in on how activities are structured to facilitate comprehension of the what of learning. Emphasis is placed on how students interact with the content.

- Audio and digital versions of text

- Organization (graphic organizers)

- Kinesthetic access (building models, skits, songs, and movement)

- Instructional arrangements (small group, partner shares, whole group)

Product

This addresses the how of learning, specifically how students will demonstrate what they know. Instead of essays and multiple-choice tests, students may create:

- Posters

- Speeches

- Skits

- Venn diagrams

- Slide presentations

- Time adjustments for completed assignments

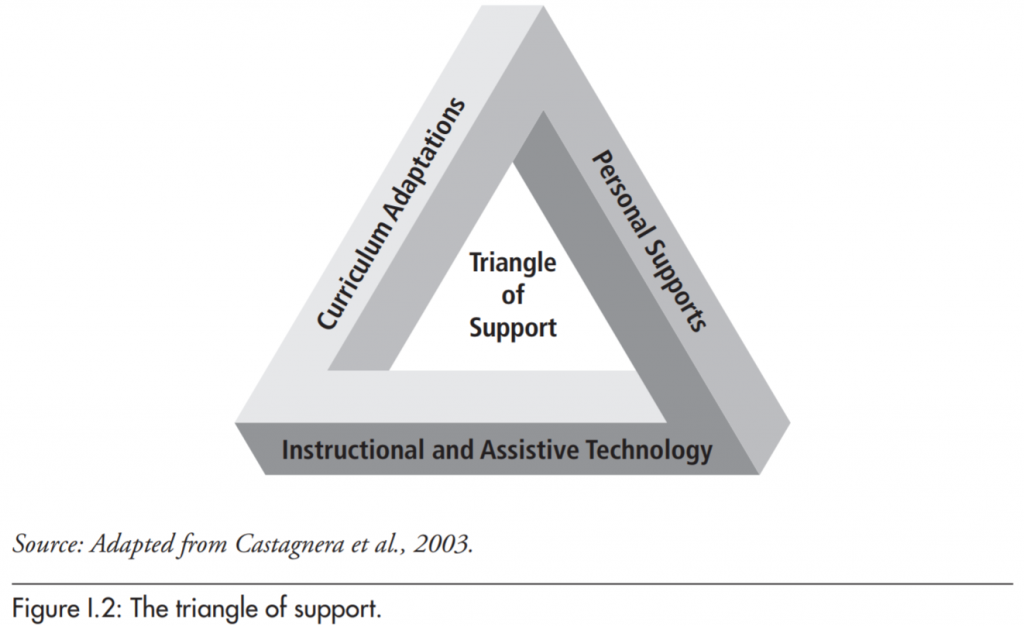

The Triangle of Supports: Ensuring Students’ Needs Are Met

In order for students to be successful in general education classrooms, the Triangle of Support highlights three essential areas that must be explored and then subsequently provided as needed: Curriculum Adaptations, Personal Supports, and Assistive Technology (Castagnera, Fisher, Rodifer, Sax, & Frey, 2003). Curriculum adaptations includes accommodations and modifications that meet the needs for specific students per their Individualized Education Program (IEP). However, when teachers address the needs of all students through the use of differentiated instruction and curriculum, oftentimes many individualized adaptations are already being provided. The importance of differentiation as an essential component to student success cannot be underestimated.

Types of Differentiation: What Might It Look Like?

Differentiation within a classroom should always maintain rigor while providing a variety of adaptations that allow all students access to the curriculum. Based on formative assessments, educators determine what type of differentiation would best meet the needs of their students. Differentiating the content, process, and product all involve the provision of choice and resources to students. How it looks and the extent of differentiation depend on the activity and the students’ needs. It is critical to remember that as students gain the knowledge they need, the amount of differentiation will change. There is a wide variety of differentiation types that should be considered, and they can overlap, depending on student needs.

| Type of Differentiation | What it means… |

| Same, Only Less | Reducing the amount, while still maintaining rigor |

| Streamlined Curriculum | Focusing on key points

(e.g., graphic organizers, define key terms, clear and concise information, guided questions) |

| Same Activity with Infused Objective | Incorporating an important objective/goal needing additional instruction or practice |

| Curriculum Overlapping | Allowing components of one assignment to be used in another assignment |

| Instructional and Assistive Technology | Providing technology access, including software and websites |

| Personal Supports | Providing support from another individual, such as a peer (e.g., collaborative group learning, partner work) |

| Extension | Increasing the depth of content |

| Enrichment | Providing meaningful options centered on students’ interests |

| Compacting | Allowing students to move quickly through content they know |

| Scaffolding | Breaking content into chunks |

| Environmental Changes | Managing the climate of the classroom and providing choice for work spaces |

(Pineda Zapata & Brooks, 2017).

| Mr. Lamberto teaches a fifth-grade class filled with inquisitive minds and diverse learning needs. He embraces each of them and, through formative assessments, determines individualized supports. Mr. Lamberto is teaching a lesson on early explorers during the 1700s and 1800s, and students are producing a written reflection. He utilized a variety of graphic organizers (Streamlining the Curriculum) during his instruction, based on student needs. This served as both visual and organizational support for a variety of students. The information was presented in a variety of ways, using these graphic organizers as anchors for the content being presented.

He also provided a clear and concise visual PowerPoint (Streamlining the Curriculum) that included the definition of key terms (Streamlining the Curriculum) for students who required it. He delivered the content in bite-sized chunks (Scaffolding), as well as providing an audio and digital version of the text (Instructional and Assistive Technology) he was teaching. When students worked during guided and collaborative instruction, they were given a choice to utilize peer support (Personal Supports) as well as their Chromebooks, using features such as text to speech, word prediction, and an online dictionary (Instructional and Assistive Technology). During independent practice, students had an option to choose the type of graphic organizer (Streamlining the Curriculum) they wanted for their written reflections and a choice of the workspace within the classroom: individual desks, floor cushions, or tables (Environmental Changes). Dalia, an English language learner in the classroom, is working on making predictions. Mr. Lamberto designed a graphic organizer with guided questions (Streamlining the Curriculum), which served as prompts to incite her thinking of the events she had just studied and remain focused on key points. For the final product, students were given the choice of a poster, PowerPoint, written essay, or speech (Enrichment). Since Amber has some difficulty with expressing her ideas in writing, she chose to depict her thoughts by cutting out different events and objects having to do with these historical figures. She then arranged them in the silhouette of a man, which represented the explorers. Since this task took longer than anticipated, the art teacher, Mrs. Rocio, invited this project into her art class (Curriculum Overlapping), as they too were studying the same era. In collaboration, both the art teacher and Mr. Lamberto were able to use curriculum overlapping to support the student’s need for extended time, while still helping the student meet the requirements of both classes. Further, for other students who chose the essay, the required length of the written reflection was based on each student’s individual needs (Same, Only Less). Mr. Lamberto noticed that while Tara and Trent were very capable students, they often lost interest in classroom assignments. Trent loves math and is interested in accounting; therefore, Mr. Lamberto designed additional prompts for Trent to use during his written assignment that focused on the finances of the early explorers. Tara wants to be a fashion designer, so Mr. Lamberto had her include in her written reflection information pertaining to the attire of the early explorers. He found that giving them a variety of additional resources, such as specific books and websites along with prompts geared toward their personal interests (Enrichment and Extension) increased their level of engagement and excitement for the content and assignment. |

Let’s return to the tapas restaurant. We cannot let ourselves regress into what is comfortable. The thriving diversity in our present-day classrooms requires us to step out and explore different ways of meeting the unique needs of our learners. As educators, we are not in the business of mass production. The systems-thinking lens and our role as system managers allow us to understand that, although students may begin their learning in one place, they engage and end at different levels throughout the execution of every lesson. Making a shift to a student-centered approach and focusing on shaping the individualized learning of students involves putting our trust in differentiated instruction. This is done by recognizing what each of our students’ learning styles, interests, strengths, and areas of need are and how we can leverage them to maximize their learning.

References:

Brooks, R. & Pineda Zapata, Y. (2017). Ensuring accessible curriculum for all: What’s your objective? [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://www.solutiontree.com/blog/accessible-curriculum-and-accommodating-students/

Castagnera, E., Fisher, D., Rodifer, K., Sax,C., & Frey, N. (2003). Deciding what to teach and how to teach it: Connecting students through curriculum and instruction (2nd ed.). Colorado Springs, CO: PEAK Parent Center.

Fisher, D. & Frey, N. (2015). Unstoppable Learning: Seven essential elements to unleash student potential. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

Pineda Zapata, Y. & Brooks, R. (2017). Adapting Unstoppable Learning: How to differentiate instruction to improve student success at all learning levels. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

Thousand, J., Villa, R. A., & Nevin, A. (2007). Differentiating instruction: Collaborative planning and teaching for universally designed learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

[author_bio id=”1327″][author_bio id=”1328″]