Driving Question: What Helps Teachers Enrich Learning Through Project-Based Learning (PBL)?

When talking with teachers who have the freedom to plan their lessons and projects so that students make many choices about what, how, and when they learn, this driving question is unnecessary. These teachers know and do what it takes to promote the work the thoughtful students do. They also know the benefits.

But what happens when teachers feel they are denied any chance to make their own choices about what they will teach, on what schedule, or with what instructional tools? How do they discover the potential power of maximized student learning? They may be able to fantasize about the benefits, but they know they are not yet singing in the choir.

IT DOES HAPPEN.

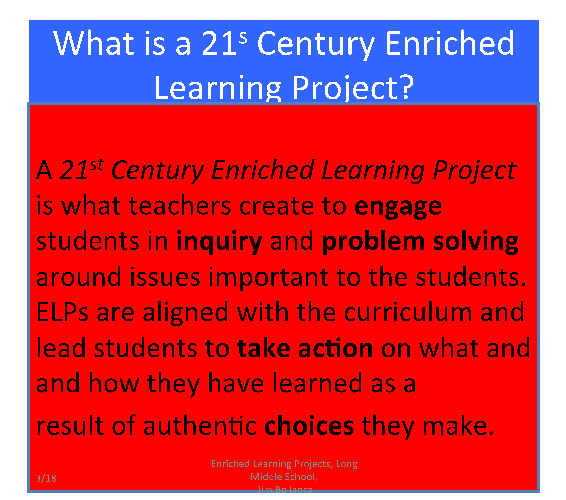

For those in the choir, those teachers in schools rich with daily PBL, it may be hard to imagine a world without student choice, problem solving, integrated technology reflection, or any features which enrich the project to provide the best of 21st century learning. Believe me, if you are in one of those schools, many of which are featured in the P21 Blogazine (www.p21.org/blogazine), you are enjoying a very special treat. You also are guided by a definition that spells out the key elements of an enriched learning project.

CONNECTING THE ENRICHED PBL-STEM DOTS

Several times in the past few months, I have taken on the challenge to help pre-K-12 faculties explore the value of making sure every STEM and STEAM classroom is driving students to the deeper learning that exemplifies 21st Century learners. For me, there is no clearer path to those deep dives than the enriched project-based inquiry pathway.

Whenever I take on this challenge, I try to walk the talk. I start with the assumption that neither STEM nor STEAM are all about more content from these important disciplines. Equally important is how the students are lead to think and act like scientists, mathematicians, engineers, and technology specialists. Thinking and acting like depends on the instructional models I use.

PBL is my instructional choice for these adult learners, just as it is for the students they teach. Even faced with a short time slot, it’s my job to make learning-from-doing in an enriched learning project the norm. My method for a three-hour introduction to PBL? A mini enriched learning project. Here is a sample:

- Our driving question: “What will happen if we switch how we are instructing STEM now to the PBL model?

- My guiding questions: “What is PBL? Why is it important for STEM or STEAM? What are my aims? How is PBL instruction done?”

- The entry activity: I asked the teachers in these schools to watch two videos. The teachers are drawn from all disciplines taught in the school, including second languages, special education, the arts, foreign languages, PE, as well as the STEM subjects, to watch Worms to Wall Street and Technology at High Tech High.

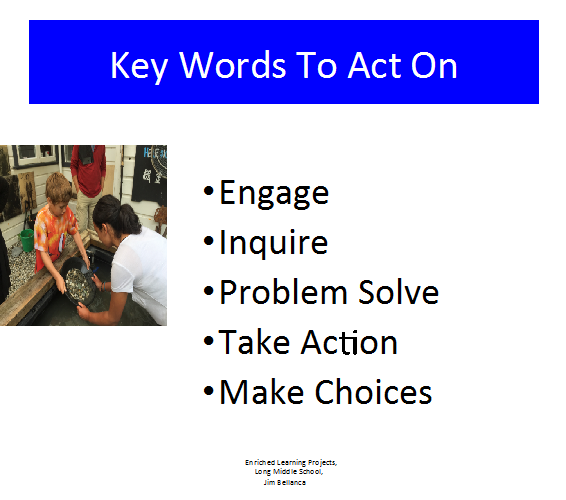

- Making sense: After teams of three complete a T-chart noting what learning looked like and sounded like in these videos, I asked them to group their responses on a graphic matrix with five headers. “Which actions and sounds fit with these key words, the defining attributes of 21st Century Learning?”

THE NEED TO KNOW ARISES

As each teacher shared an action observed and matched the example to a key word, it is not long before their needs to know emerged.

“I loved the choices the children had. But we can’t do that.” Murmurs of assent.

“Amen.”

“I would love to do inquiry. There just isn’t time. The fast kids answer fast, but the others eat up the clock as I have to pull ideas from them.”

“I think I already do these things. My science units give the kids a page of key words with good examples. They read these and then we discuss them. I also have them use a concept map so they connect the concepts. In my wind unit, we do experiments in the lab so they can get a feel for the different ideas and then they complete the workbook in teams. I even let them study in teams.”

“I was just awed at those little kids doing all that planning. I don’t know where to start.”

“I always use teams in my labs. I give them roles and guiding questions so they can get ready for the unit exam.”

“I have centers for our science theme. Students get to pick which centers they are interested in.”

“Those are the types of science projects I wish I had tine to do.”

“I set up my computers in the back of the room. I’m not like HighTech High. I only have three. I let all the kids take turns to play the games and answer research questions.”

“I give them lots of choices with learning packets. They pick the ones they like and I encourage them to ask questions.”

As I listened, I noted on the white board each item they selected. When all had said what they wanted, I selected my next question so that I could refocus the teachers away from the impediments they were seeing. I wanted them to see that most, if not all, were missing signs of deeper learning that were in their classrooms. I knew if the teachers could uncover what they had experienced, or what they let their students experience, that they would be more hopeful in giving choice and voice, focusing on problem solving and so forth. After all, the two video examples had come out of well-developed school environments with veteran PBL teachers at work. These teachers were in a different place.

What followed in the responses about their own experiences showed them that “yes, indeed” they and their students were making decisions, solving problems, being engaged together, albeit in some cases, with small choices. Granted, many examples, such as letting students pick which book to read for a report or which partner with whom to dissect a worm, were small and random. But there were some bigger fish too.

- A drama teacher designed a project for her class to write its own musical play – building the sets, scoring the songs, holding tryouts, and presenting at an all-school assembly. The catch? The theme had to focus on how technology was changing the students’ lives. “But they had lots of choices,” she affirmed.

- A science teacher assigned teams to make and test their own weather instruments. “I stayed away. If anything, I coached on the side.”

- A math teacher challenged his students to build robots, as long as they incorporated the statistics he was teaching. “I saw the need to get boredom out of statistics.”

The reality was that digression from a daily schedule in which students were to ingest so many pages of the textbook and answer chapter questions, listen to lectures, take formative quizzes every Friday, and finish worksheets for homework was the well-worn pathway for most of the teachers. Although some felt comfortable slipping in some student choice, most struggled to follow the principal’s expectations to stay on a schedule and get kids test ready, NOT college and career ready. “I don’t feel I have choice. I can’t take the time to have them work in groups or to do some of the other things I saw. I would love to. I think my students would love it, but it’s not the name of our game.”

MULTIPLE QUESTIONS OF HOW

At this point, it was clear that the positive examples from colleagues raised interest in the “how” question. They were ready to express what they needed to know. The multiple needs to know were loud and clear, just begging to be recorded. A sample:

- “How do I make a bigger switch from being in charge to giving student voice?”

- “How do we convince our principal that student choice is a great motivator?”

- “How do I start a PBL that I can fit into my time schedule?”

- “How do I get used to letting kids be messy as they work on projects and make their own choices?”

- “How soon do I let them make a driving question about a topic not in my curriculum?

- “How many guiding questions do I make and how many do they make?

- “How do we get the time to do the planning this looks like it needs?”

The multiple questions of “how” told me that these teachers did “get it.” They grasped the motivational power behind agency for students. They were ready to move down the path toward a different way of teaching that could engage their students in making choices about important problems, choices that could readily match up to the curriculum and the students’ learning needs.

THE READINESS IS ALL

Shakespeare’s Hamlet got it when he declared the “Readiness is All.” The “it” for these teachers was “the need to know the how to weave agency into daily instruction.” My experience has told me that whether learners are first graders or seasoned classroom veterans, when students’ learning needs come to the fore, my job of teaching is half-done, well begun.

For the rest of our 140-minute time, I was ready to help these teachers choose their way forward. Although this awareness session lacked the time to plan a full single week, multiple-discipline PBL, as shown in the video examples, a small four to five hour design would foment chances to increase student choice in standards-aligned STEM content. Here’s how we moved ahead:

First, I asked grade-level teams to analyze the Whale of a PBL (P21 Blogazine, March 1, 2016) from Katherine Smith Elementary School. How did the teacher engage the students?

Second, we returned to the five keys slide (see above). Through all group discussion, we developed how they might transform that design into a five-hour mini-project. Here are several samples formed by the teacher teams.

- Engage: Start our next lesson with a hypothetical question. (e.g. Life Cycle: “What do you think will happen if you have to tell a story about the life cycle of a whale?”)

- Inquire: After hearing at least seven different responses, ask the class to vote on the answer with which they most agree. Ask follow up questions so that teams of three can go on line and research their answers.

- What are the periods in the life cycle of the whale?

- How long would it have to live?

- Predict what problems you would have growing up if you were that whale.

- What is the worst thing that could happen to this whale in its lifetime?

- How is the whale’s cycle the same or different from yours?

- Problem Solve: Let each student team select one of the predicted problems and suggest solutions that would help the whale survive.

- Take Action: Let each team sketch the whale in the various periods of life. Instruct them to make measurements so they can show the real size in numbers and label all parts.

- Make Choices: Instruct each team to choose and present what it thinks are the three more important times in their whale’s life.

Third, the teachers and I assessed the do-ability of the mini-project designs. We followed by using the five keys as a rubric for what they had just done with the life cycle topic. How engaged were the students? What percentage of the learning time went to inquiry? To problem solving? To reflection?

Lastly, we reflected forward. I asked them to think about how they might repeat this process to develop 21st Century learners. Although some were still concerned about the principal’s receptivity, all but two thought it doable.

A TAKE AWAY PROBLEM

I left them with the problem to figure out that last question – how they could increase the principal’s receptivity. Now they had knowledge of the how-to tools for the classroom. Now they also had the readiness to start doing by selecting tools for their own mini-projects. They had discovered their own voices and the intrinsic worth of making their own choices. Now they knew that it was possible to transfer agency to their students in ways that they would choose, and incorporate the five keys into manageable projects.

Down the road, I felt they were ready to continue in their grade-level teams to plan more full-blown PBL units filled with the five keys. As they deepen their understanding of agency with additional learn-by-doing lesson plans and mini-projects, they will see how their own agency can increase and they will ask and assess how their students can take advantage of this powerful tool to promote inquiry and problem solving.

For those in STEM classrooms, they now had a good idea of the tools they would need. For their colleagues in a STEM-centered school that taught other subjects, the readiness was all they too needed to start students on the pathways of thinking and learning like 21st Century citizens.

[author_bio id=”145″]

Hello,

I am a student at ASU in a teacher program. I am wondering how budget plays into creating this type of curriculum. It seems like there were a lot of tangible items being used for creative purposes. How can teachers from low-income schools accomplish this?

Thanks.