“People are tied together and yet isolated from each other by invisible threads of rhythm and hidden walls of time.” —Edward T. Hall

Most global educators have a challenging relationship with the “Fs of Global Education.” The Fs, which include cultural facets such as food, festivals, flags, and fashion, are those elements of culture we can see most easily. There’s nothing wrong with exploring the observable aspects of culture, of course, but staying there can create superficial learning experiences, even leading to cultural misrepresentation and stereotypical assumptions about other cultures.

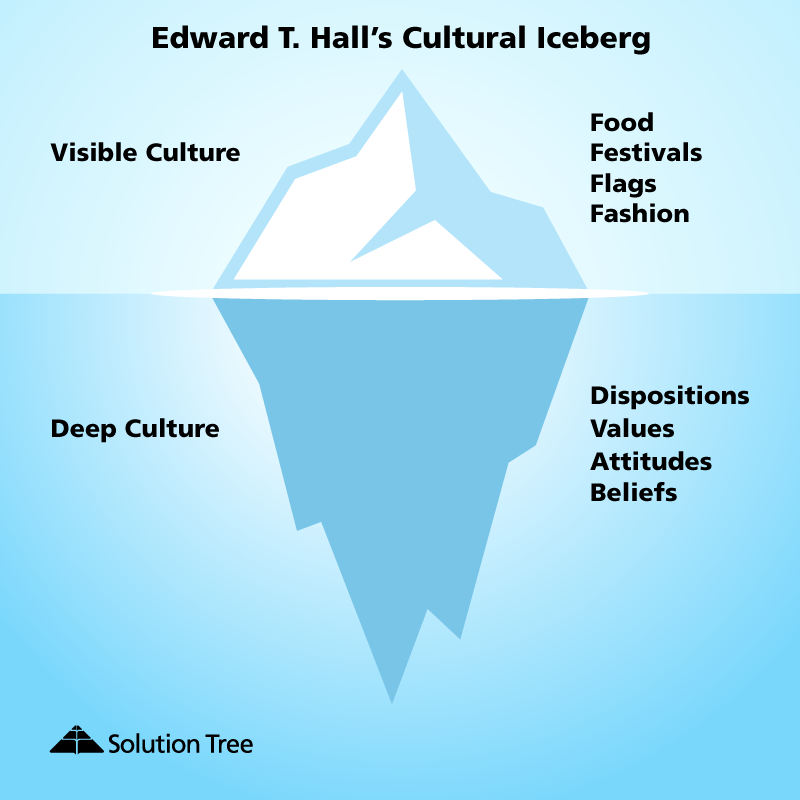

The Cultural Iceberg

In Edward T. Hall’s 1976 book, Beyond Culture, he explores what he calls “The Cultural Iceberg Model.” According to Hall, just as we can only see 10 percent of an iceberg above the waterline, 90 percent of what we call “culture” isn’t visible above the surface. While we can observe facets such as fashion, flags, and food, deeper elements of culture such as dispositions, values, attitudes, and beliefs provide a more nuanced look at culture. In fact, when we dig beneath the surface of the Fs, we often find the reasons behind what we can see on the surface.

Our goal as global educators should be to dig beneath the waterline as much as possible, and global partnerships can help us do exactly that. It’s not that we should avoid the Fs in our classrooms, but that we should ensure students’ inquiry delves deeper into the complexities that “culture” and the human experience include.

4 Ways to Move Toward Teaching Deep Culture

Following are a few suggestions for how you might move beyond the Fs in your classroom.

-

Consider the Fs an entry point, not an end point.

The Fs are alive and well in many elementary and world-language classrooms, and there’s nothing wrong with that. I still remember the first time we made molé in my Spanish classroom as a middle schooler, and I loved cooking Costa Rican empanadas with my students. The Fs are a starting place, an entry point that students enjoy; but if we stop there, our students miss an opportunity for deeper learning. What are the geographic and cultural reasons behind the fact that Mexican foods are spicy (more or less so depending on the region), while Andean foods in South America rarely are? Instead of just cooking or eating foods from a different region, digging beneath the Fs means investigating the history of local cuisines, why a given region uses the ingredients they do, and how those foods connect to culture and daily life.

-

Dig beneath the Fs by asking why the surface elements exist.

It’s not that the Fs are a superficial element of a culture at all, really, but we have to ask why they exist if we want culture to be more than a festival. Why do traditional Chinese fashions use so much red, for example? What are the origins of the Nigerian flag, and does it still represent Nigerian cultures accurately today? In one of my favorite projects, Global Partners Junior, students around the world collaborated to understand and share their country and local flags with each other. They investigated the history of their flags and considered the extent to which they still represented the identity of their regions, ultimately redesigning their local flags. This takes the topic of flags, which is often just a reflection of nationalism, to a much deeper and more meaningful level—and it allows students to be critical and creative thinkers who have a voice in their sense of self and community.

-

Connect with real people to bring the Fs—and other topics—to life.

Until your students engage with real people who practice the Fs in their day-to-day lives, the likelihood is high that students will continue to make assumptions about the cultures they explore. In order to break down such stereotypes, we should develop global and local partnerships that bring students into direct contact with new people, perspectives, and cultural practices. While I know that many teachers enjoy dressing up in the “costumes” of a given culture, even using the term “costume” suggests that understanding the fashion of a place is more like playing dress-up than exploring reality. Instead, a partnership can connect your students with actual people living in those cultures, and suddenly questions about their daily clothing versus traditional clothing can add nuance to the conversation.

Many years ago, through my Fulbright Memorial Fund experience in Japan (predecessor to the Fulbright Education for Sustainable Development program), I had the chance to watch a kabuki actress transition from her regular street clothing to full kimono and traditional makeup. It was one of the most powerful things I’ve ever watched; she talked about each step of the process and gave us the history of each element of her dress, makeup, and hair. She took questions during lulls in her narrative, and the whole experience took about three hours from start to finish. The experience humanized my sense of Japanese theatre and traditional dress very deeply, and it ignited a love of traditional kimono dress, makeup, and hairstyles. It was a learning experience I’ll never forget, in part because it dove so far beneath the surface.

-

Move beyond the Fs by digging into deeper global and intercultural challenges.

We have a myriad of global challenges on our planet that need to be addressed collaboratively, ideally by conscientious young changemakers who might find new solutions to them. Framing a global partnership or other experience around the Sustainable Development Goals (also see Teach the SDGs), the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, or the Convention on the Rights of the Child takes teachers and students into meatier topics. They also provide a framework for student choice and a legitimizing foundation in school contexts where social-justice topics are considered controversial.

These global challenges don’t preclude cultural explorations; for example, many wars and conflicts around the world originate in differences of culture, as we’ve seen in South Africa, Rwanda, Israel/Palestine, and many other contexts. If you need a less-intense starting place, for younger learners or because of potential resistance in your community, consider investigating how we might protect against climate change or another borderless problem. Such projects and partnerships could include learning about indigenous cultures that don’t contribute to global warming, to see how their way of life provides a better road map to sustaining life on our shared planet.

The bottom line is that we have to do more than just dip our toes into the water; to really dig beneath the Fs of global education, we need to haul out the scuba gear and be prepared to take a much deeper dive. Global progress requires not just collaborative, multilateral development, but also the sort of nuanced understanding that helps us see how much we have in common and learn from what we do differently. If all we ever engage is what we can see on the surface, we will continue to stereotype and assume. Instead, we need to foster a different sort of engagement founded in questioning, investigating, and understanding, so that global progress is informed by all the richness of those beliefs and values found beneath the waterline.