I’m learning to read.

No, really. I’ve learned so much about learning to read while studying contracted braille for about two years now. While I may be able to read large print for many more years, a degenerative eye disease is slowly stealing my sight. And, it’s definitely easier to move from sight to touch while you can still see.

From dots to words: the fascinating world of reading braille

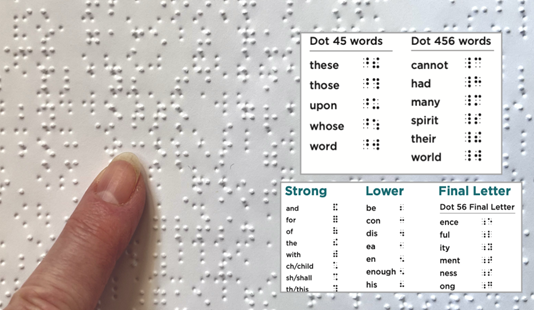

Learning contracted braille is a bit like moving from phonemes to phonics to words to sentences to stories. The braille alphabet is made up of different six-dot formations in “cells” that combine to form words. In contracted braille, there are shortcuts. For example, in basic braille, you use the symbols for t, h, and e to spell the. In contracted braille, a single symbol means the and there are many such single symbols. You can see some of the contractions in the image below.

Further, add one dot in front of that symbol for the and it means there. Two dots? These. Three dots? Their. The word other? It’s o, then the the symbol, then r.

Mastering braille, one humorous anecdote at a time

Like a beginning reader, skills practice came first. I completed all 78 workbooks, every single exercise. I made flashcards to master what is pretty much a code to crack with my fingers, not my eyes. I was very content with the short sentences and reading passages in the workbook, whatever the subject. I was motivated to develop the skills.

To continue practicing reading braille, I subscribed to the braille edition of Reader’s Digest—its short articles and humorous anecdotes were ideal. At first, I read word for word. Then one day, I began a passage on hot honey—a condiment made by infusing honey with hot chili oil. I’ll never make it, I thought, since my husband would consider his beloved honey ruined if I did!

The article went on with an involved description of the author’s experiences with using hot honey. I started wondering how long the article was and used my fingers to skim for the symbol that starts a new article. Eight pages in total.

With my skill level, reading braille at this pace took about 30 minutes per page. Arithmetic told me the article would consume four hours of my life. And there was no way it was worth it! I skipped the rest and continued with the next section of short “Laughter is the Best Medicine” jokes. Whew!

The key to better reading

My educator brain kicked in and I thought, If I, an adult motivated by my own autonomous choice to learn reading braille, cannot make myself read this article, what does that say about children learning to read? Once the excitement of those first literacy experiences fades, why would a child who is struggling with skills do the hard work, as braille is for me, of practicing if the content is of no interest?

I made a decision to read only the articles that intrigue me, partly because the monthly issues keep arriving before I’ve finished the prior month’s. Motivated now by both the need for skills and pleasurable content, I’ve increased my speed from 30 to 10 minutes per page. It’s getting to be way more fun!

Nurturing both reading skills and a love for books

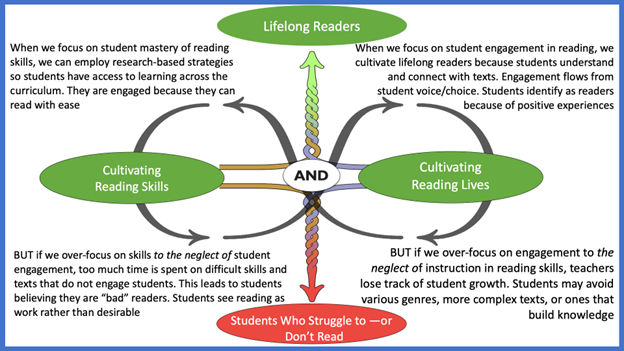

What does this mean for reading instruction? There is an interdependency between even the best instruction in reading skills AND ensuring that students are enjoying reading. We want them to see it as a desirable way to spend their time so that they look forward to reading an internet article or a book or other material.

Motivation comes through engagement, yet one seldom engages deeply if one doesn’t have the skills. We are kidding ourselves if our reading programs do not acknowledge this ongoing tension. In fact, ignoring either component of reading instruction—developing skills AND developing a love of reading in our students—will result in students reading at lower levels. Swinging back and forth between these interdependent factors is the source of the reading wars.

Do I sometimes need to read things that don’t interest me? Of course, but I am a mature adult with executive function—I can find a purpose, whether I need to read for background knowledge or for book club or so that I can connect with someone who is interested in the topic. Students who are struggling to read aren’t necessarily ready to self-motivate in this way.

What will it take to get us to see this interdependency?

Look at the diagram below. Perhaps helping students find motivation is an action step on the left side. Or having students listen to less motivating texts or read with a partner might be action steps on the right side. In other words, instead of saying, “Well, students simply have to read this,” we strategize to help them do so.

What are your “have to’s” for students and reading? Have you taken a “side”? Please consider the limitations of your position, the strengths of the other, and focus on taking action to keep the right balance – ensuring our students become both skilled and eager readers.

About the educator

Jane A. G. Kise, EdD, is the author of more than 25 books and has extensive experience in leadership development, executive coaching, instructional coaching, and differentiated instruction.