This is the sixth post in a series on student-led, small-group discussions. To read the other posts, see “Small Groups, Big Discussions.” The series explores the challenges to effective small-group discussions and how to address them.

As you prepare for a year filled with many opportunities for students to talk, you may reflect on your past experiences and wonder how you might enhance your classroom environment to set students up for successful experiences with student-led discussions. Four things come to mind when I think about the rituals and routines that need to be present for students to engage in meaningful talk.

- The classroom climate must value student voice.

- We need to understand what quality discussions look and sound like.

- We need to explicitly teach students group-membership behaviors and communication strategies while expanding their knowledge of important content.

- To engage in meaningful dialogue, students need to read, view, and listen, to deepen their knowledge of important content.

1. Classroom Climate

When setting up a discourse-rich environment and one that enhances student engagement, both the physical and emotional environment should be considered (Garcia, n.d.). Students need to feel their voice matters when they speak in the classroom. There are things we can do to signal that the classroom is a place where student talk is valued and supported. When you enter the classroom, what does the physical environment and emotional culture look and sound like?

Seating

Are desks in rows or clustered together? Are tables or pods used instead of desks? Are there spaces for whole-group, small-group, and independent application?

To build a collaborative environment where students speak often, as educators we need to be able to transition often and quickly among the instructional modes of whole groups, small groups, and pairs. Desks in rows signal isolation and take valuable time to move each time students are asked to talk together. Tables, pods, or clusters of desks work well in setting up a classroom rich with student talk.

Classroom Library

Is there a classroom library where students have ready, fingertip access to books that could be used for the current unit of study? Are electronic resources available for students to use?

To have meaningful dialogue, students need information to talk about that extends beyond the content provided by the instructor during whole-group instruction. They need to read from a variety of resources, to extend the contributions each member makes to the group. Access to an abundance of books within the classroom results in increased motivation and increased reading achievement (Guthrie, 2008; Routman, 2014; Worthy & Roser, 2010).

Talk Prompts

When I walk into Lisa Swanson’s fifth-grade classroom, I see talk prompts hanging from the ceiling and often displayed on the Smart Board before students begin their discussions. This display signals to all that they will receive support as they develop their communication skills.

Examples of the generic talk prompts that can remain all year may include:

- Tell me more.

- I can add on to that idea.

- Can you clarify that point by providing an example?

- What examples from our book, our experiences, or the world can we provide?

Talk prompts can also be specific to the communication skill students need to learn. For example, if we want students to offer opposing views without being confrontational, we can offer support that results in a healthy, robust discussion, rather than an argument.

Examples in order of sophistication include:

- I disagree with that statement because _____________________.

- _____, you stated (paraphrase). In this resource (show text) it states (paraphrase text evidence). So, I think that means _____________.

- I agree with (explain the point of agreement), but have you considered ____?

- A counterpoint to that statement is ______________ because (state evidence). Can we determine a mutually acceptable agreement?

Anchor charts

As we lead a whole-group focus lesson, it is important to model or think aloud when we demonstrate the communication learning target. After the modeled lesson, the students, along with assistance from the teacher, can use chart paper to generate the communication strategies and processes used during the lesson.

This chart paper should be displayed for students to refer to when they begin to apply this skill in their conversations. The use of this visual can help students organize and deepen their conversation. At the beginning of the year, you might ask students to help develop a list of group-membership behaviors and post the chart for all to see as behaviors are modeled, demonstrated, and applied throughout the year.

2. The Look and Sound of Quality Discussions

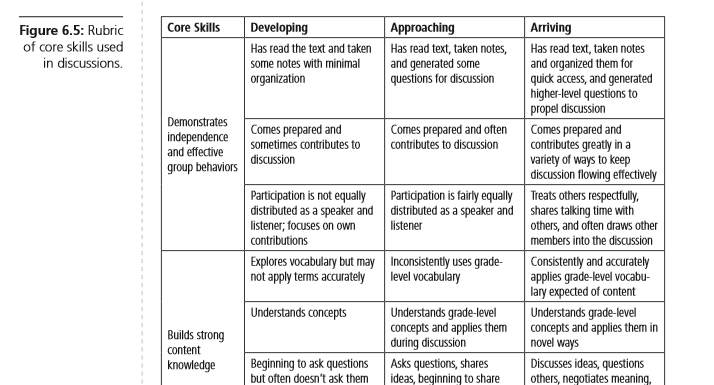

When thinking about our students’ progress as they engage in discussion, we should be mindful of the stages of their developing skills. You might consider developing a rubric for students to be able to assess their level of progress. Developing rubrics helps clarify the expectations you and others have for student performance by providing detailed descriptions of those agreed-upon expectations. In our book, Deep Discourse: A Framework for Cultivating Student-Led Discussions, we offer an example that lists three levels of performance—developing, approaching, and arriving—that serve to more fully describe the core skills needed for rich, fruitful discussions (Novak & Slattery, p. 132–133). You may wish to refer to it as you create your own rubric.

3. Content and Communication Skills Instruction

We know that communication skills are important during student-led discussions, but we might wonder how we find time to teach these skills during an already-packed school day. One way teachers have found successful is to teach both a content and communication learning target during the same mini-lesson. Consider the following ninth-grade example.

Social studies learning target: I can read and gather five pieces of evidence from at least two credible sources to support my argument for or against immigration.

Communication learning target: I can listen attentively and respond to a group member’s specific claim, evaluate the soundness of the evidence, and follow up with an appropriate probing question.

During the focus lesson, the teacher highlights the important statements in the text on the Smart Board as he rationalizes his position for immigration. After he states his position and supports his claim with credible evidence, he models how a group member might respond. He uses sentence frames that have been written in advance. As he uses them, he displays them for all students to see and use later while they practice the skill.

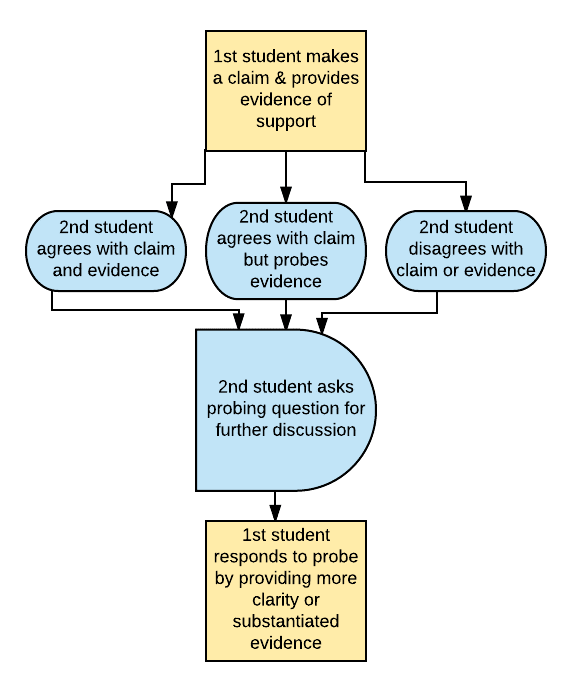

Graphic Organizer of Process

While this modeled lesson takes only about ten to fifteen minutes, it is important to supplement the experience by highlighting the process students need to learn and apply later in their small- group discussions. For this topic, the structure of how students might communicate the required elements could be displayed in a flow chart. One example follows:

When students have a structure to follow, they are more apt to stay on topic and engage in meaningful dialogue. The more initial support we offer, the greater the likelihood of positive outcomes.

Use of Protocols

Students need assistance building their repertoire of communication skills. We offer protocols that give support as students are initially taught these skills.

In the social studies example, students need to listen to a group member’s claim, evaluate the soundness of the evidence, and follow up with an appropriate probing question. When a student makes a claim against immigration, a student might ask the probing question, “What would need to change for immigration to be advantageous to the United States?”

Developing good questions on the fly when students are in groups is a challenge for most students, no matter their grade level. The School Reform Initiative’s website offers over 100 protocols for learning communities that teachers have also used with students. The Pocket Guide to Probing Questions offers examples of questions that we can teach and model for students. Later, they may use it as they ask a probing question.

4. The Value and Importance of Reading

The frequency and volume one engages in reading impacts the development of a wide variety of cognitive capabilities, including verbal ability and general knowledge (Cunningham & Zibulsky, 2014). We cannot expect students to contribute to a discussion if they have limited background knowledge about a topic.

Students have several ways to attain information to talk about with their peers:

- They can listen as we share information during a lecture.

- They can view videos about the content that we provide or they retrieve on their own.

- They can read the content we provide or that they research on their own.

Regardless of how the information is attained, discussions cannot happen until students have some general knowledge about the topic.

The routines we set at the beginning of the year can help transform some students’ non-reading habits into desirable practices. When preparing for the first unit of study, we can offer structured choice in their reading material and make sure they know they will be talking with their peers about their selection. They will be more motivated to read if they know they will have a chance to talk about their reading with peers. The collaborative, interactive nature of small-group discussions enables all students—including reluctant readers and English learners—to find the support they need to fully engage with texts (Fountas & Pinnell, 2012).

Setting up your classroom environment for student discussions, preparing for them, and offering lots of opportunities for dialogue at the start of the school year will lead to a year when you reap the riches of your preparation. Your students will engage in academic conversations with refined communication skills while developing a deeper understanding of important content.

References:

Cunningham, A., & Zibulsky, J. (2014). Book Smart: How to Develop and Support Successful, Motivated Readers. Oxford University Press.

Fountas, I., & Pinnell, G. (2012). Comprehension Clubs. New York: Scholastic.

Garcia, L. (n.d.) “How to Get Students Talking! Generating Math Talk That Supports Math Learning.” Retrieved from http://www.mathsolutions.com/documents/how_to_get_students_talking.pdf on May 18, 2017.

Guthrie, J. (2008). Engaging Adolescents in Reading. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Novak & Slattery. (2016). Deep Discourse: A Framework for Cultivating Student-Led Discussions. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree.

Routman, R. (2014). Read, Write, Lead: Breakthrough Strategies for Schoolwide Literacy Success. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

School Reform Initiative website accessed at http://www.schoolreforminitiative.org/protocol-alphabetical-list-2/ on June 12, 2017.

Worthy, J., & Roser, N. (2010). “Productive Sustained Reading in a Bilingual Class.” In E. Hiebert & R. Reutzel (Eds.), Revisiting Silent Reading: New Directions for Teachers and Researchers. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Next time, I answer the question, “What group membership skills should I explicitly teach?” Look for the blog post on September 28!

Sandi Novak, an education consultant, has served as an assistant superintendent, principal, curriculum and professional development director, and teacher. She has authored three books: Deep Discourse: A Framework for Cultivating Student-Led Discussions (Solution Tree, 2016), Literacy Unleashed (ASCD, 2016), and Student-Led Discussions (ASCD, 2014). She also authored the online ASCD PD course, Building a Schoolwide Independent Reading Culture, as well as journal articles and blogs. Visit Sandi’s website, join her professional LinkedIn community, or send her a tweet @snovak91335.

[author_bio id=”1117″]