Do you have a way of living during the summer that’s different from the rest of the year?

We do. We spend time outside grilling and going for walks. We read more books. We get in a nap while our children are off at their summer activities, we see friends more often, and we get more writing done than in any other season. And it’s not just us. We have a friend, a seventh grade English teacher who’s also a mixed-media artist, whose summer days mostly involve gluing unicorns to painted canvases. Another teacher friend spent one summer road-tripping from New York to Panama.

Many teachers catch up on professional development, reading articles they’ve been saving, and if their school budgets allow, attending summer institutes. And because our profession is not the most lucrative, we know plenty of teachers who have temporary summer jobs—but they too go might into summer mode during their afternoons, evenings, and weekends.

What is it about summer that allows us to live so fully? More to the point, what is it about September that stops us?

We might say we have no time for such luxuries as reading and naps during the school year. We’re too busy to see friends and too stressed to concentrate on art projects. We’re too tired for a long walk, and anyway, it’s not as nice outside.

Cultivating summer well-being during the school year

But for the very reasons that we abandon our summer mode of living, we need it. During the school year, when we’re tired and busy and stressed, and when the cold weather and reduced daylight puts us in low spirits, is precisely when we most need to exercise, connect with others, play, relax, and in all other ways take care of ourselves. So why don’t we?

During the school year, we have more goals to orient our attention. When we’re pursuing a particular goal—getting a unit planned, a stack of essays graded, a student disciplined—our attention tends to focus narrowly on achieving that goal (Gilbert, 2010). Teaching also presents all kinds of challenges: forgotten meetings, lockdown drills, crying students, angry emails, acts of violence. These daily challenges can threaten our sense of safety, competence, and control. When we feel threatened, our attention tends to focus solely on avoiding the source of threat (Wilson, 2009; Wilson & Murrell, 2004).

When we have a goal, our minds say, “Get it!” and under threat our minds say, “Get it away!” We’re focused on that “it,” and nothing else. But without goals and threats to capture our energy, our attention tends to widen (Gilbert, 2010). As teachers, with fewer immediate goals and threats during the summer, our attention can expand to include our personal needs. Is it possible to train our capacity for flexible attention during the school year, too?

Bringing summer into the new school year

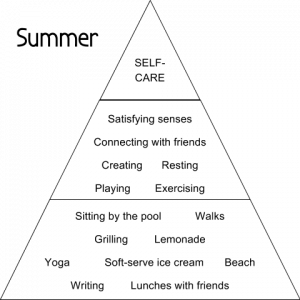

What if, instead of thinking of the summer activities we enjoy—whether it’s hiking, fishing, or seeing a friend—as summer, we think of them as self-care? When we frame the activities as parts of summer, then in order to get the sense of fulfillment and vitality they provide, we we have to wait for summer. But if we frame those same activities as parts of meaningful self-care, then we can look for activities in other seasons that serve those same self-care functions.

Some activities are only fun during summer: we could join a community center with an indoor pool, but that wouldn’t be nearly as satisfying as a dip on a 94-degree day. But the point isn’t to find ways to go swimming in the winter; it’s to discover that sense of fulfillment that summer provides. By focusing on the function of our favorite summer activities rather than the form, we might think more flexibly about what self-care can mean year-round.

The activities we love during summer might serve some of the following self-care functions:

- Resting

- Playing

- Exercising

- Connecting with loved ones

- Nourishing our bodies

- Satisfying our senses

- Learning

- Creating

- Being in nature

- Preventing illness and injury

You might find some of these functions more important than others, and you might think of categories of self-care beyond the ones listed (such as practicing mindfulness). Some activities might serve multiple functions: going to the beach might be an opportunity to rest, play, exercise, and connect with friends.

Try this: Draw a pyramid with three levels.

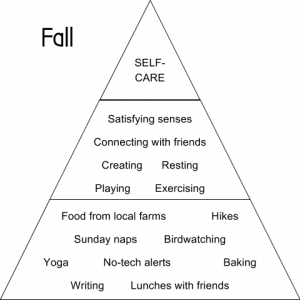

At the bottom, list some of your favorite summer activities. What important categories of self-care do they belong to? (By important, we mean important to you.) Write those categories in the middle of your pyramid and “self-care” at the top. Now that you’ve created the top levels of your self-care pyramid, can you use them to help you imagine other, seasonally appropriate activities that would fulfill these same functions in the fall? What about winter and spring?

For example, in the fall we could look for migratory birds as a way of being in nature, get produce from a local farm as a way of satisfying our senses, and set alerts on our electronic devices to remind us to disconnect from the demands of school so we can connect with each other. While these activities might not be as fun as the beach, we can notice them as opportunities for self-care.

You might try the self-care pyramid exercise with your students, too. Like us, many students have fewer demands on their attention during the summertime—and notably, some are more stressed during the summer because of food insecurity, family situations, jobs, and other demands. Either way, discovering opportunities for year-round self-care might elicit a more empowering conversation than, “What did you do over the summer?”

About the educators

Jonathan Weinstein, PhD, is a clinical psychologist with the Northport VA Medical Center in New York. He has served in various mental health and education roles and has adapted elements of contextual behavioral science to help teachers empower students.

Lauren Porosoff is the founder of EMPOWER Forwards, a collaborative consultancy practice. An educator since 2000, Lauren has written and presented extensively on how students and teachers can make school a source of meaning, vitality, and community in their lives.

References:

Gilbert, P. (2010). The compassionate mind: A new approach to life’s challenges. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.

Wilson, K. G. (2009). Mindfulness for two: An acceptance and commitment therapy approach to mindfulness in psychotherapy. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.

Wilson, K. G., & Murrell, A. R. (2004). Values work in acceptance and commitment therapy: Setting a course for behavioral treatment. In S. C. Hayes, V. M. Follette, & M. M. Linehan (Eds.), Mindfulness and acceptance: Expanding the cognitive-behavioral tradition (pp. 120–151). New York: Guilford Press.