Based on Behavior Solutions: Teaching Academic and Social Skills Through RTI at Work™

First came RTI, then RTI², and now there’s MTSS.

What’s different? What changed?

As we support schools across the country, we are faced with many districts, even state departments of education who treat RTI as a bad word, rather than taking an honest look at the understanding, misconceptions, and implementation errors.

We’ve heard, “Whatever you do, don’t call it RTI; we call it MTSS now,” or “RTI is a bad word in our state, and Tier III is only for special education.” We can go on and on with a long list of misconceptions. Unfortunately, new names (what we refer to as “rebranding”) for essentially the same initiative simply clouds implementation, leads to additional misconceptions, and muddies the water even further.

We will use this commonly asked question to guide our case: How is RTI² different from RTI/MTSS? (We use RTI and MTSS interchangeably.)

The answer to this question is pretty straightforward: RTI/MTSS and RTI² are not different. If schools across the country were implementing RTI correctly initially, there would be no need to add to or change terminologies to make it seem “more comprehensive.” The answer to this question is not an attempt to make provocative statements or elicit emotional responses from those with strong feelings toward one definition over the other. It is simply to help educators avoid falling into the RTI rebranding trap we have seen much too often.

Here are two ways to avoid falling into this RTI rebranding trap.

1. Understand the definition and key components of RTI before adopting the same thing with a different name.

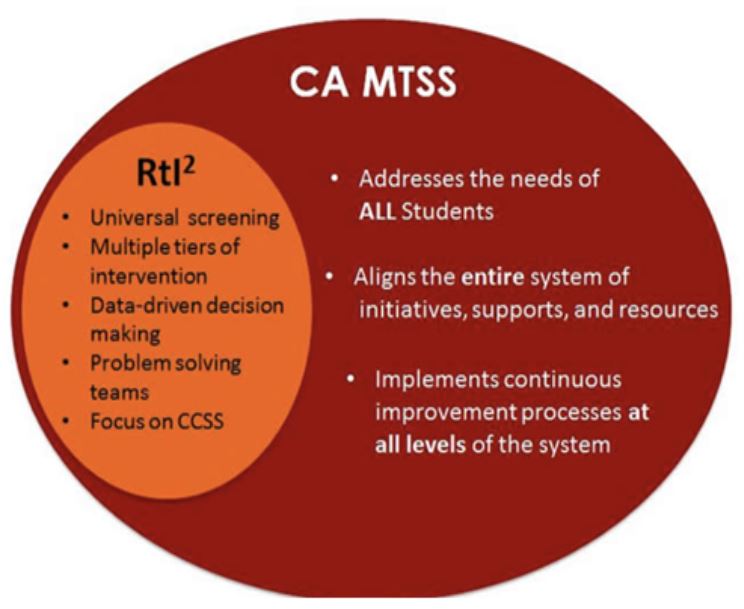

First, let’s look at one example of similarities and differences between California’s MTSS and RTI² processes from the California Department of Education in Table 1.1 below.

Keep in mind, this is one example of the lack of clarity around this topic that is happening similarly in other states across the country. Also keep in mind, although we use MTSS and RTI interchangeably, it does not necessarily mean California does. In fact, in this particular example, you will see how MTSS is compared to RTI² , and there is no mention of RTI; yet all of the key components highlighted in MTSS and RTI² are and always have been a part of an effective RTI framework.

Table 1.1: CDE MTSS and RTI² Comparison

| MTSS Differences with RTI² | MTSS Similarities to RTI² |

MTSS has a broader scope than does RTI². MTSS also includes:

|

MTSS incorporates many of the same components of RTI², such as:

|

According to the similarities listed in the above example, both rely on RTI data-gathering through universal screening, data-driven decision making, and problem-solving teams, and are focused on the Common Core State Standards. However, it is stated that the MTSS process has a broader approach, addressing the needs of all students by aligning the entire system of initiatives, supports, and resources, and by implementing continuous improvement processes at all levels of the system.

We respectfully disagree that this is a new concept. We would argue that any current-model RTI school would also have such structures firmly in place for both academics and behavior; hence, why we use RTI/MTSS interchangeably. Based on this comparison example, it is clear there is a disconnect/misunderstanding of the core components of RTI, which has led to this progression of rebranding the terms from RTI, RTI², and now MTSS.

2. Audit the understanding, implementation, and alignment of your past and current RTI practices

More than likely, the next implementation (no matter what you decide to call it) will produce the same unenthusiastic outcomes, since the core components of RTI were not implemented as intended in the first place.

To make matters even more confusing, see the figure 1.1 diagram, which provides a visual of how MTSS is “more comprehensive” than RTI².

Figure 1.1: Venn Diagram of MTSS and RTI²

Buffum, Mattos, and Weber (2009) stated in Pyramid Response to Intervention: RTI, Professional Learning Communities, and How to Respond When Kids Don’t Learn that the only way for an organization to successfully implement RTI practices is within the PLC at Work® process. You cannot effectively implement RTI without the PLC process. The three big ideas drive the work of a PLC: a focus on learning, a collaborative culture, and a results orientation. The progress a district or school experiences on the PLC journey will be largely dependent on the extent to which these ideas are considered, understood, and ultimately embraced by its members (DuFour et al., 2016).

The three big ideas further emphasize the connection between MTSS and how it pertains to PLCs and RTI.

A focus on learning

The fundamental purpose of the school is to ensure that all students learn at high levels (DuFour et al., 2016). Because proper student behavior is also a prerequisite to academic success, a professional learning community would commit its collaborative efforts to ensure all students master essential academic and social behaviors in addition to essential grade-level standards.

A collaborative culture

In order to ensure all students learn at high levels, educators must work collaboratively and take collective responsibility for the success of each student. The fundamental structure of a PLC is the collaborative teams of educators whose members work interdependently to achieve common goals for which members are mutually accountable. These common goals are directly linked to the purpose of learning for all (DuFour et al., 2016). While grade- or course-specific teacher teams drive the identification and teaching of essential academic standards, the entire staff must work collaboratively to identify and teach essential behaviors.

A results orientation

To assess their effectiveness in helping all students learn, educators in a PLC focus on results. The constant search for a better way to improve results by helping more students learn at higher levels leads to a cyclical process in which educators in a PLC.

- Gather evidence of current levels of student learning

- Develop strategies and ideas to build on strengths and address weaknesses in that learning

- Commit to collective inquiry to learn about best practices to address the school’s area(s) of weakness

- Implement these research-based strategies and ideas

- Analyze the impact of the changes to discover what was effective and what was not

- Apply new knowledge in the next cycle of continuous improvement (DuFour et al., 2016)

Table 1.2: Comparing the MTSS broad approach to the 3 big ideas of a PLC

| MTSS | 3 Big Ideas of a PLC |

| Addresses the needs of ALL students | A focus on learning:

The fundamental purpose of the school is to ensure that all students learn at high levels. |

| Aligns the entire system of initiatives, supports, and resources | A collaborative culture and collective responsibility:

In the PLC at Work process, we do not refer to each site team as a “PLC”—the entire school is considered the professional learning community. It will take a collective knowledge and skills of a school staff—including classroom teachers, administration, and support staff—to ensure every student succeeds. In short, a PLC aligns the entire system.

The fundamental structure of a PLC is the collaborative teams of educators whose members work interdependently to achieve common goals for which members are mutually accountable. These common goals are guided by four critical questions:

(DuFour et al., 2016, p. 36) |

| Implementing continuous improvement processes at all levels of the system | A results orientation:

The constant search for a better way to improve results by helping more students learn at higher levels leads to a cyclical process in which educators in a PLC:

|

While educators across the country are trying to wrap their heads around another new framework (MTSS), know that MTSS is aligned to the three big ideas and four critical questions that drive the work of a PLC. The goal should not be to create a new initiative under semantically similar constructs, but rather to focus on how to improve the implementation of what nearly 20 years of research has already proven to be effective, which is being anchored by the three big ideas and four critical questions that drive the work of a PLC—all of which is amplified through RTI/MTSS.

Additionally, RTI has been highlighted as one of the top educational practices proven to considerably accelerate student achievement—by two to three years’ growth within a single year of schooling—with an effect size of 1.29 (Hattie, 2017). Best practices would be to exemplify the PLC and RTI process as intended and with fidelity, rather than calling it by another name and hoping for a different outcome the second time around.

Your road map to MTSS

Learning by Doing is the gold standard to the PLC process. Taking Action is a comprehensive resource that essentially takes chapter 7 from Learning by Doing and builds the RTI at Work™ framework, giving educators actionable steps to creating multi-tiers of systematic supports in their schools for academics and behavior. Behavior Solutions is a comprehensive resource that will provide a road map for creating behavior systems in every tier by expanding on the work in Taking Action (chapter 4 for Tier I, chapter 6 for Tier II, and chapter 7 for Tier III). Use this graphic below to visualize your road map toward MTSS:

Rather than focusing on what to call it today (RTI, RTI², or MTSS) or in another five years, the focus should be on how these schoolwide systems encompass all the essential actions for both academics and behavior at the prevention, intervention, and remediation levels, based on data to help all students. Implement the resources in Taking Action and its behavior companion Behavior Solutions to understand how RTI/MTSS for academics and behavior are connected, while requiring educators to function as a PLC (Learning by Doing) for implementation to be successful. This process will perfectly prepare your school/district for the next possible rebranding—MTSS².

[author_bio id=”1372″]

Jessica Djabrayan Hannigan, EdD, is an assistant professor in the Educational Leadership Department at California State University, Fresno. She works with schools and districts throughout the nation on designing and implementing effective social and emotional/behavior systems. Her expertise includes response to intervention (RTI) behavior, professional learning communities (PLC), multitiered system of supports (MTSS), positive behavior interventions and supports (PBIS), restorative practices, social and emotional learning (SEL), and more.